Lucy Kalanithi and Stephen Grosz in conversation

Recorded at Waterstones in Hampstead, Lucy Kalanithi, widow of Paul Kalanithi, talks to psychoanalyst and author Stephen Grosz about her husband’s memoir When Breath Becomes Air.

Karl Ove Knausgaard and Stephen Grosz in conversation, May 2014

Stephen Grosz reads his story ‘Through silence’

Medicine Unboxed, November 2013.

BBC Radio 3: Private Passions with Michael Berkeley

In conversation with Michael Berkeley, Stephen Grosz tells his own story: his childhood in Chicago, the son of immigrants who ran a grocery store; student days in radical Berkeley; and now, settled in Britain, how he’s facing the challenges of fatherhood and ageing. Music has played an important part right from the beginning, and Grosz admits that his choice of music is very psychologically revealing.

In conversation with Michael Berkeley, Stephen Grosz tells his own story: his childhood in Chicago, the son of immigrants who ran a grocery store; student days in radical Berkeley; and now, settled in Britain, how he’s facing the challenges of fatherhood and ageing. Music has played an important part right from the beginning, and Grosz admits that his choice of music is very psychologically revealing.

NPR: Weekend Edition with Rachel Martin

NPR: Weekend Edition with Rachel Martin

Dreams. How we describe our dreams can be more important than what they contain. Host Rachel Martin talks with Stephen Grosz, a practicing psychoanalyst and the author of The Examined Life: How We Lose and Find Ourselves. Grosz uses dreams to better understand his patients’ motivations and feelings.

BBC Radio 4: A Good Read

Stephen and Meera Sayal talk with Harriet Walter about Chekhov, Agatha Christie and Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers. August 2013.

NPR: On Point

NPR: On Point

Stephen Grosz in Conversation with Jane Clayson in for Tom Ashbrook, July 2013. This hour, On Point: deep into the mind with The Examined Life.

Book Talk

Literature on the Couch: Stephen talks to Cary Barbor at Book Talk

[soundcloud id=’98590952′]

RTE 1 Today With Pat Kenny

RTE 1 Today With Pat Kenny

Pat Kenny is joined by Professor Jim Lucey, Medical Director with St Patrick’s psychiatric hospital and Clinical Director of Psychiatry in Trinity College to discuss “The Examined Life” (Monday 8th April)

Radio New Zealand

Radio New Zealand

Stephen discussing his book “The Examined Life” on Radio New Zealand’s Saturday Morning with Kim Hill

Profiles & Press Interviews

Two People Not Knowing Together

An Interview with Psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz

An Interview with Psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz

(by Jessica Gross, The Brooklyn Quarterly, October, 2014.)

In twenty-five years as a psychoanalyst, Stephen Grosz has spent more than 50,000 hours listening to his patients’ stories. His first book, The Examined Life, published last year, presents a selection of these in beautiful and incisive prose. (As Michiko Kakutani put it in an enthusiastic review, the book reads “like a combination of Chekhov and Oliver Sacks.”) The portrayals of his patients’ struggles and changes, thanks to the talking cure, accrue over the book into a powerful case for the psychoanalytic process. Jessica Gross spoke to Grosz, who lives in London, by phone last year. The first part of that interview follows below.

Jessica Gross: It took a few decades for you to decide to write a book. Can you tell me about that process?

Jessica Gross: It took a few decades for you to decide to write a book. Can you tell me about that process?

Stephen Grosz: I’ve written technical papers for analytic journals, and I always liked analytical presentations, but I didn’t like the format of our scientific journals. Talking is more convincing than any outcome study, and I wanted to find a way to get that on the page. Another thing is, I am sixty, I got married at fifty, my daughter is ten and my son is seven. With parenting, you are very aware of death and loss. My mom died at sixty-four and my father had heart attacks. There was something about that that was very motivating. I wanted to do two things: write something my kids could read when they were eighteen or so, and give them a picture of a kind of disposition toward the world. That is maybe the thing that I find hard explaining to people who haven’t been in analysis. I hoped that the book would leave them a picture of my way of thinking about things. (read the full interview)

The Stories We Tell Ourselves

(by Mandy Van Deven • In the Fray • September 9, 2013)  I didn’t expect a collection of stories about the inner struggles of psychoanalysis patients to be so much like a detective novel. Yet, in The Examined Life parallels abound. Clues are uncovered slowly in each chapter and a mystery unfolds. Hidden motivations are unearthed by identifying the meaningful in the mundane. The skillful narrator walks the reader through his ruminative process of making sense of the clues. A truth is revealed that appears to have been there are along. Psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz has penchant for storytelling. He knows when to showcase his professional proficiencies and when to let the tale tell itself. The truth, after all, is somewhere in-between. What was your motivation in embarking on this project? I am sixty. I have a ten-year-old daughter and a seven-year-old son. My father had two heart attacks by the time he was my age, and my mother died when she was sixty-four. If I’m not here when my children are teenagers or young adults, I thought about what I want them to know. The thirty-one stories in The Examined Life address what I think of as some of life’s biggest problems — problems we all face. More than that, I wanted to portray a way of thinking, a disposition towards oneself and the world that might be useful to them and others. Also, psychoanalysis requires time and money, and many people won’t be able to afford it. I wanted to set down some of the important things I’ve learned in a way that may be helpful to those who are unable to have psychoanalysis or therapy. (read more)

I didn’t expect a collection of stories about the inner struggles of psychoanalysis patients to be so much like a detective novel. Yet, in The Examined Life parallels abound. Clues are uncovered slowly in each chapter and a mystery unfolds. Hidden motivations are unearthed by identifying the meaningful in the mundane. The skillful narrator walks the reader through his ruminative process of making sense of the clues. A truth is revealed that appears to have been there are along. Psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz has penchant for storytelling. He knows when to showcase his professional proficiencies and when to let the tale tell itself. The truth, after all, is somewhere in-between. What was your motivation in embarking on this project? I am sixty. I have a ten-year-old daughter and a seven-year-old son. My father had two heart attacks by the time he was my age, and my mother died when she was sixty-four. If I’m not here when my children are teenagers or young adults, I thought about what I want them to know. The thirty-one stories in The Examined Life address what I think of as some of life’s biggest problems — problems we all face. More than that, I wanted to portray a way of thinking, a disposition towards oneself and the world that might be useful to them and others. Also, psychoanalysis requires time and money, and many people won’t be able to afford it. I wanted to set down some of the important things I’ve learned in a way that may be helpful to those who are unable to have psychoanalysis or therapy. (read more)

On Therapy, Literature and Understanding Obama

(interview with Daniel Lefferts from Bookish.com, June, 2013)

Bookish: Your book is a collection of short stories about patients, and storytelling plays role in your therapeutic approach, as well. Describe the relationship between narrative and psychoanalysis. Stephen Grosz: The people who come to analysis are in great pain, and usually part of the pain is that they can’t articulate it well. They don’t have a way of telling it. Often, the most important stories of our lives are about some of the most difficult things that no one helped us to find the words to describe. [In analysis,] you try to hear [the patient’s] stories and work out what’s going on. All the highfalutin psychoanalytic language—which is not in my book—is, to me, a diversion from the directness of literature—hearing people’s stories, and trying to put that story as clearly and as plainly on the page as possible. Bookish: Was it your aim, in writing “The Examined Life,” to help people? SG: The best thing a book can do to help us feel a new thing or think a new thing. One of the reasons I love Andrew Solomon’s book, “Far From the Tree,” [is because] I have not met one person who’s read that book and not changed how they thought. I tried to write things that would change how people think. The issues I chose had a kind of urgency, because they are the things my friends and I talk about, my wife and I talk about, my children and I talk about, my patients want to know about. They are the most pressing problems. I felt I had something to say about them, or that the patients had taught me something that I wanted to show. (read the full article)

Psychoanalysis as Literature: Stephen Grosz’s ‘The Examined Life’

(by Lucy Scholes, The Daily Beast, June, 2013)  I’ve always found psychoanalysts slightly awkward interview subjects. This is perhaps unsurprising when it comes to men and women who must be somewhat of a blank slate. Talking about oneself invariably doesn’t come easy to someone whose job is to listen. As such, I’m momentarily thrown when Stephen Grosz proves himself the perfect interview subject, engaged, engaging, warm, and not averse to sharing his feelings. But then what should I have expected? I’m here precisely because his first book, The Examined Life: How We Lose and Find Ourselves, defied expectations by achieving the seemingly impossible: a book about psychoanalysis that made the bestseller lists in the United Kingdom, a country where Freud is readily dismissed as a quack. This volume, now out in the U.S., is a distillation of Grosz’s 25 years of practice, from which he amassed over 50,000 hours of conversation, into 31 chapters, each a peek into the human psyche. One of the chapters begins with the story of Mary. Mary is the 46-year-old married mother of three. One day she and her husband attend a neighbor’s garden party, during the course of which she strikes up a conversation with another guest, Alan, a widowed barrister. The two share stories of grief—his wife’s recent death, her sister’s—and agree to meet for lunch at Alan’s house the following Friday. “When Friday arrived,” Grosz writes, “Mary showed up at his doorstep with a bouquet of peonies, a bottle of Sancerre, and a removal van containing all of her clothes and possessions, including some large pieces of furniture.” Alan refused to let Mary into his home; she broke down in the street, crying and screaming, so Alan called her husband, who in turn contacted the family doctor. What became of Mary, we’re never told. Grosz doesn’t deal in neat resolutions, nor in diagnoses. “It’s not as simple as that,” he says. In the book’s preface he quotes the philosopher Simone Weil’s description of how two prisoners in adjoining cells learn to talk to each other by tapping on the wall. “The wall is the thing which separates them, but it is also their means of communication,” she writes. “Every separation is a link.” Grosz says the book is about the wall. “We tap, we listen,” he writes. (read more)

I’ve always found psychoanalysts slightly awkward interview subjects. This is perhaps unsurprising when it comes to men and women who must be somewhat of a blank slate. Talking about oneself invariably doesn’t come easy to someone whose job is to listen. As such, I’m momentarily thrown when Stephen Grosz proves himself the perfect interview subject, engaged, engaging, warm, and not averse to sharing his feelings. But then what should I have expected? I’m here precisely because his first book, The Examined Life: How We Lose and Find Ourselves, defied expectations by achieving the seemingly impossible: a book about psychoanalysis that made the bestseller lists in the United Kingdom, a country where Freud is readily dismissed as a quack. This volume, now out in the U.S., is a distillation of Grosz’s 25 years of practice, from which he amassed over 50,000 hours of conversation, into 31 chapters, each a peek into the human psyche. One of the chapters begins with the story of Mary. Mary is the 46-year-old married mother of three. One day she and her husband attend a neighbor’s garden party, during the course of which she strikes up a conversation with another guest, Alan, a widowed barrister. The two share stories of grief—his wife’s recent death, her sister’s—and agree to meet for lunch at Alan’s house the following Friday. “When Friday arrived,” Grosz writes, “Mary showed up at his doorstep with a bouquet of peonies, a bottle of Sancerre, and a removal van containing all of her clothes and possessions, including some large pieces of furniture.” Alan refused to let Mary into his home; she broke down in the street, crying and screaming, so Alan called her husband, who in turn contacted the family doctor. What became of Mary, we’re never told. Grosz doesn’t deal in neat resolutions, nor in diagnoses. “It’s not as simple as that,” he says. In the book’s preface he quotes the philosopher Simone Weil’s description of how two prisoners in adjoining cells learn to talk to each other by tapping on the wall. “The wall is the thing which separates them, but it is also their means of communication,” she writes. “Every separation is a link.” Grosz says the book is about the wall. “We tap, we listen,” he writes. (read more)

A Psychoanalyst’s Tale

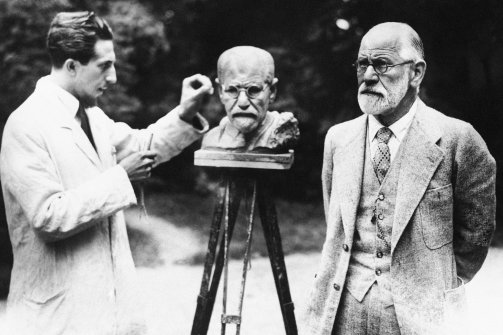

(from The Guardian, January 7)

After practising as a psychoanalyst for 25 years, Stephen Grosz has written a book – of the stories his patients learnt to tell on the path to recovery

After practising as a psychoanalyst for 25 years, Stephen Grosz has written a book – of the stories his patients learnt to tell on the path to recovery

There’s a lot of the literary in Stephen Grosz. You can tell from the chapter titles of his book, with their familiar fireside whiff of Aesop or Kipling: How Lovesickness Keeps Us From Love; How Anger Can Keep Us From Sadness. Often, too, his limpid, pared-down fables conclude with an observation so elegant and so penetrating that it is almost an aphorism: Better to have lost something than be something someone forgot; Closure is the false hope that we can deaden our living grief. It’s no accident, of course. The story is at the heart of psychoanalysis, the profession Grosz has practised, with distinction, for 25 years. Sigmund Freud saw this, asserting more than once that his case histories read strangely like novellas rather than bearing the “serious stamp of science”. (read more)

On Parenting

(Sunday Times, 13 January 2013)

(Sunday Times, 13 January 2013)

A horror of criticising our children leads to an equally harmful practice, a top psychoanalyst explains to Sian Griffiths Collecting his daughter from nursery one day, Stephen Grosz overheard the assistant tell her: “You’ve drawn the most beautiful tree. Well done.” A few days later he heard her say of another drawing: “Wow, you really are an artist.” On both occasions, writes Grosz in The Examined Life, his first book, “my heart sank. How could I explain to the nursery assistant that I would prefer it if she didn’t praise my daughter?” It seems an extraordinary statement. Why would a father — and a psychoanalyst, to boot — not want his daughter to be complimented? Sitting in his consulting rooms in Hampstead, northwest London, Grosz pours me a cup of tea before answering. “Admiring our children may temporarily lift our sense of self-esteem but it isn’t doing much for a child’s sense of self,” he says. “Empty praise is as bad as thoughtless criticism — it expresses indifference to the child’s feelings and thoughts.” (read more)